The Maine legislature is deliberating over a bill to become the 16th state to enter the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact and the fourth state to do so in the past few months. Under that bill, once states with a majority of electoral college votes (270) adopt the Compact legislation, they will direct their electors to cast their ballots for the presidential candidate who earns the most votes, nationwide. At that point, every vote in the country, including in those states that have not joined the Compact, will count equally. Accordingly, Maine’s consideration of this legislation has attracted national, international, and now even Solar System attention.

A Martian visitor here in our small town outside of Augusta, Maine, the state capital, who conscientiously studied American government from the red planet before coming here, sought me out to inquire how our government works in practice in order to complement his research back at the University of Mars. This is an edited transcript of our conversation.

EM: So let’s start at the top, because how you select your national leader is almost impossible to figure out from the documents available to us on Mars. You consider your country a democracy but the people don’t vote for the President.

Me: They do vote for the president. Officially they vote for the electors in their states. But the electors are pledged to a specific presidential candidate, and then the electors vote for that candidate. It is that second step in the process that determines who becomes president. In other words, the people elect the president indirectly through the electors.

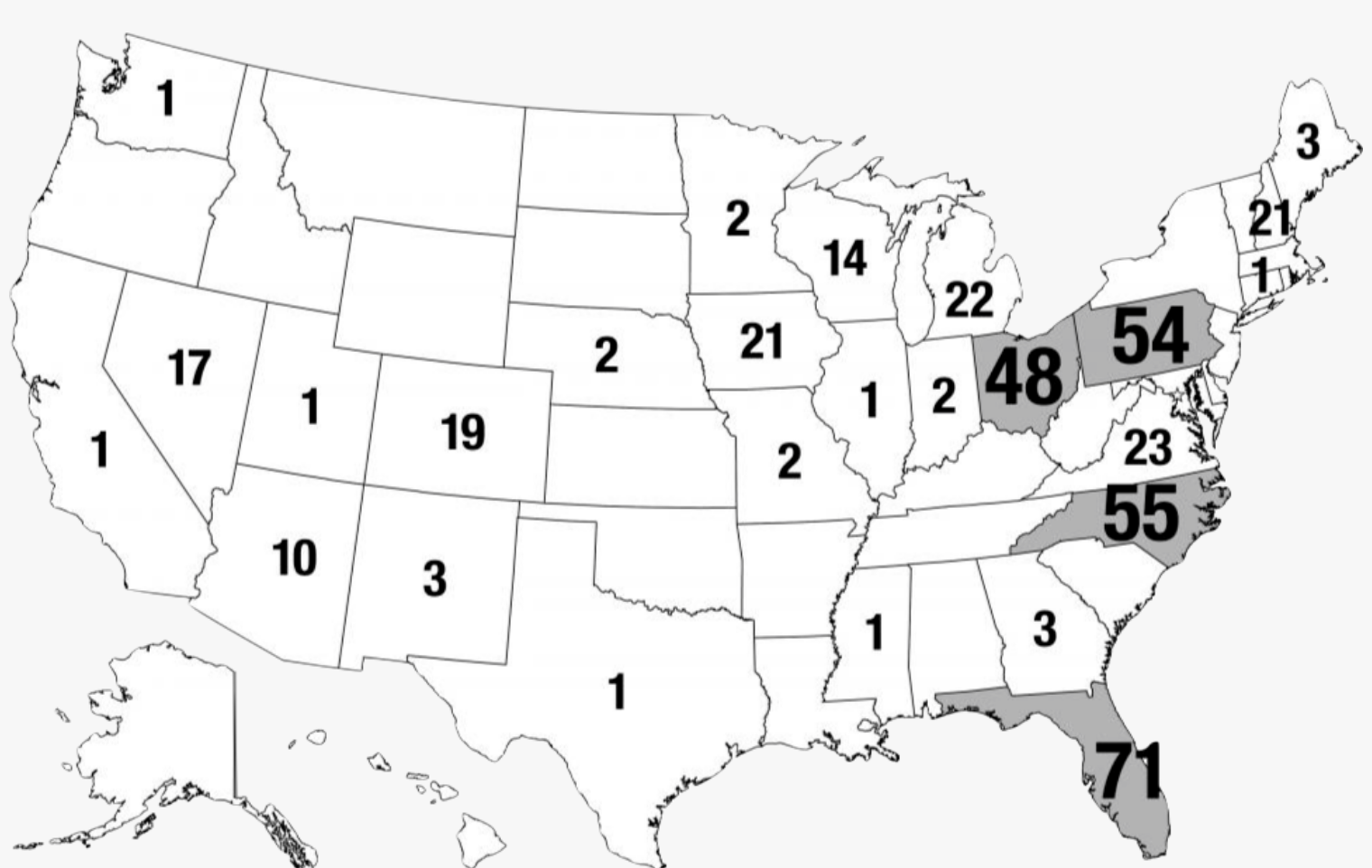

EM: Well, that answer is somewhat helpful. But a state’s voters are voting only for their state’s electors. There is nothing national in that first step of the election process. Moreover, we Martians know that, in the second step the votes of each state’s electors in 48 out of 50 states are aggregated on a winner-take-all basis. As a result up to 49% of the votes in that state have no relevance or weight in the actual election of the President.

Me: I can’t argue with that, but the reality is that almost every American voter thinks he or she is voting for the president.

EM: Back on Mars, we researched the litigation that Harvard Professor Lessig has brought in several states challenging, under the equal protection provision of the Constitution, how they allocate their electoral college votes. In one of those cases, the State of Texas defended its winner-take-all system on the grounds that the so-called presidential election is, as a legal matter, an election among competing slates of electors, not among presidential candidates.

Me: Well, put that way, the legal processes does seem to be inconsistent with the view of nearly every American that he or she is voting for the president.

EM: Even more difficult to understand is that Texas, like many other states we researched, has a law forbidding the state from identifying the names of electors on their ballots. How do you justify that?

Me: I can’t. All I can say is that our country’s founders were very smart men, and what was good enough for them is good enough for me and for most Americans.

EM: Now I am really concerned. We Martians also admire your founders, but our research shows that the system of state electors that the founders had in mind bears no resemblance to the election system that your country has in place now. The founders expected that electors would be venerable “wise men” from each state who would join with their counterparts from other states in Washington DC to deliberate over who should be elected president. When a state’s electors were selected in the early years of the country (and the states used several different ways to select electors), they were not pledged to any particular candidate – as they are today. Under your current system, electors are virtually unknown to the public and serve as passive message-carriers like the U.S. mail or an ISP. Many states have even enacted faithless elector laws that prohibit them from voting for anybody other than the candidate to whom they pledged their votes. To make my point, have you ever knowingly met an elector?

Me: No. It never seemed to matter.

EM (interrupting): See. That’s what I mean. When we Martians study the American Constitution, we admire the fact that the founders gave to the states the authority and responsibility to change how they allocate their electoral college votes as they gained experience with the process and determined what changes were needed. One of your most famous judges, also from New England, wrote an important book explaining that American law is distinctively based not on abstract logic, but on experience. And yet your states adhere to a system that experience has shown to be unfair, undemocratic, as a practical matter disenfranchises 80% of American voters and is causing rapidly escalating damage to your country.

Me: Instead of my explaining how our presidential election system works to you, I am embarrassed to confess you have explained it to me. But you have also explained to me that the states have the right under the Constitution to allocate their electoral college votes in the manner they choose. Maine is considering a bill to direct its electors to cast their votes for the winner of the national popular vote through the Compact, and I will support that bill.

EM: Now you sound like the kind of American Martians admire, one who when he or she sees a problem goes about the business of fixing it.