Here is look at the debates that gave rise to the Electoral College, and how the southern states’ desire to preserve slavery was a driving factor behind our current system (from the Milwaukee Independent).

The Civil Rights Case for the National Vote

Elaine Kamarck explained that in 2004, testifying to a Democratic commission formed to reform the nominating process, Ron Walters, a “veteran of Jesse Jackson’s two presidential campaigns,” described “how difficult it was for African American candidates” to “do well” in the “all-white states of Iowa and New Hampshire.” He said that if “Section 2 [of the Voting Rights Act] suggests that we shouldn’t dilute the voter of minorities,” then putting these two states up-front in the process has “the effect of diluting the black vote.” The reason is that the results in these two states matter more than the results that follow in later states, where the percentage of African-American votes is much higher. Page 79.

The winner-take-all system of allocating electors has the same effect. In states where African-American votes typically are cast for the losing presidential candidate, such as across the states in the former Confederacy, those votes are “diluted.” Indeed, they are systematically discarded.

The only two ways to make those votes matter equally to white votes are to have all states adopt a proportional system of allocating electors according to the popular vote in states OR to have some states allocated some electors to the national winner, thus forcing the candidates to seek a national win based on a one person-one vote principle in order to get enough electors to be president.

The former solution works only if all states adopt it. If all were willing to do that, they might as well simply amend the Constitution by calling for direct election of the president. (Americans have long favored that step, but professional politicians have stood in the way.) The latter works even if only a few states chose to allocate electors to the national winner. The way to avoid diluting any group’s votes – not just African-Americans, but any group’s votes – is for some states to allocate some electors to the national winner. There probably is a Voting Rights lawsuit to bring on this topic.

The Electoral College Makes Presidents Unaccountable

Declaring a national emergency to build a wall on the southern border is wildly unpopular. Polls have consistently shown that about 66% of Americans think that Trump should not declare a national emergency to build the wall, and only 31% think that he should.

So why would a president up for reelection double down on such an unpopular policy?

The answer is the Electoral College. The president does not need a majority of Americans to like what he is doing. All he needs to do is to turn out his base and win by a slim plurality in the few swing states that will decide the election.

If, on the other hand, the president needed to win the most votes from across the whole country, it would be unthinkable for Trump or any other president to chart a course that two-thirds of the nation opposed.

Giving Female Candidates a Fair Chance

If Senator Gillibrand is running a feminist campaign, then she might want to make this useful point: in the last presidential campaign almost ten million more women voted than did men. By a huge majority the female voters preferred Clinton. The majority of women for Clinton was bigger than the majority of men for Trump.

So what happened? How could the more numerous group of voters, with the stronger preference, not have elected their choice as president?

The only reason that the majority of women did not see their preferred candidate sworn in as president in January 2017 was the Electoral College system.

In a tiny few swing states, the female preference was a little below the national average.

If every vote counted equally and all were counted in a nationwide tally that chose the president, then women (and men) already would have had a fair chance to elect a female president.

And if Senator Gillibrand, or anyone else, wants a fair chance to be a feminist candidate, then the most important reform would be the appointment of electors to the national vote winner instead of only to the winner of statewide pluralities.

Colorado National Popular Vote Bill One Step Closer to Passing

A Colorado state House committee has voted to advance the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact to a full House vote. The bill has already been approved by the Colorado Senate. The bill will now go to a full vote in the House, and if approved, to Colorado’s governor, Jared Polis (D), who supports the measure.

If Colorado adopts the Compact, Colorado’s 9 electoral votes will be added to the 172 electors that will be pledged to the winner of the national popular vote if states with a total of 270 electoral votes join the Compact.

The National Popular Vote Would Make Every Vote Equal

In her article opposing the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, Tara Ross makes three arguments in favor of the antidemocratic unequal treatment of voters accorded by the Electoral College. First, she argues that but for the Electoral College, residents of small and midsize states would be ignored. Second, she argues that a change to the national popular vote can only be done by a constitutional amendment. Finally, she argues that if states are bound together to cast electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote, some states will be prejudiced because the rules for voting differ from state to state. None of these arguments are convincing.

The first argument makes no sense on its face. If all votes counted equally then candidates would have the same motivation to seek all votes regardless of geography. The question is not whether they would do that, but how. As we noted in another blog, advertising on social media makes it easy to reach out to potential voters all across the country, and if the popular vote winner became the president, all candidates would have to do just that. National brands like Wal-Mart and Amazon do not ignore people in smaller markets; nor would candidates seeking to get the most votes across the country.

Contrary to the argument that the Electoral College protects small states, small and midsized states are entirely ignored under our current system, except for a small number of swing states. The candidates flock to New Hampshire and Iowa, but ignore Rhode Island and North Dakota completely because those votes are taken for granted by one party or the other. Under a national popular vote system, candidates would reach out to all voters in all states.

Second, we do not need a constitutional amendment to ensure the that winner of the national popular vote becomes the president because the Constitution empowers states to allocate their electoral votes as they see fit. Article I, section 1 of the Constitution provides: “Each State shall appoint, in such Manner as the Legislature thereof may direct, a Number of Electors . . . .” In other words, the drafters of the Constitution specifically left plenary power to the states to decide how to choose the electors. Our existing, winner-take-all system is not mandated in the Constitution and is only one of a number of options a state could chose to allocate its votes. Originally, many states chose to have their legislatures choose the electors directly, without having the people vote at all, a choice they could theoretically still employ today. Maine and Nebraska have chosen to split their electoral votes by congressional districts with two votes awarded at large. Assigning electoral votes to the winner of the national popular vote is another permissible choice, and a choice that is good for the country.

Finally, differences in voting requirements from state to state is not a reason to stick with the outdated, undemocratic Electoral College. Ross notes that some states have more opportunities for early voting or make it easier to vote absentee, and states that under the Electoral College system, “no one cares if Texans have more time to early vote than voters in Colorado.” However, with the national popular vote, “a ballot cast in Texas could dictate the outcome in Colorado. Suddenly, it matters a great deal that Texans had more opportunities to vote.” This does not follow. The outcome of a vote in one state can already impact the outcome of the election for all other states under the Electoral College. Further, when only a few states matter, our elections are much more vulnerable to foreign meddling or election irregularities because it is far easier to hack an election in the three critical swing states that decided the 2016 election than in the whole country.

The current system allows the candidates to ignore the vast majority of the governed, focusing only on the small number of people living in states where the election is likely to be close. If the winner of the national popular vote became the president, the interests of rural voters in Illinois would matter as much as rural voters in Michigan, and city dwellers in Texas would matter as much as city dwellers in Florida. For these reasons, most people agree that the person who wins the popular vote should become the president.

If Candidates Had to Win the National Tally They’d Compete Everywhere

A shibboleth of the enemies of direct democracy for choosing the president is this:

If every vote mattered equally no candidates would care about the votes in less dense or rural states.

On its face this claim seems self-contradicting. If every vote counted equally, then obviously every candidate would try to get every vote everywhere. The question would not be whether they wanted every vote, but rather how would they go after the votes in less dense areas.

We already know the answer by looking at how major brands and retailers reach every possible customer.

First, retailers invest in national branding. Currently in the general election presidential candidates spend almost nothing advertising on national television shows. If every vote mattered equally this would change. You’d see the president advertising on the Super Bowl, or for that matter, stalking the sidelines for “product placement.”

Second, in major urban areas the cost of reaching customers through broadcast or cable channels is much higher than in less dense areas. Therefore campaigns would proportionally spend less on television spots in dense areas, and much more on television in less dense areas. If you own a television station in the Dakotas, you should want the national popular vote to pick the president. Similarly there’d be political advertising on local radio in rural areas, whereas today there is none from the presidential candidates.

Third, the rise of social advertising is inexorable, because social advertisers can pick the target audience with more precision than can one-to-many advertising. Especially in dense areas, social would be preferred over old school techniques. But because distance is irrelevant for social advertising, the big social firms would be a platform for reaching every voter everywhere.

Fourth, just as Wal-Mart ignores no one, so candidates would ignore no region in their search for votes. Very likely, in right-leaning states the effort to get out the vote for the Republican nominee would go up, because the Republicans currently gain nothing by seeking higher turn-out in the more rural states where they are the preferred party.

Fifth, there is some evidence already that confirms these hypotheses. This is from the estimable web site Nationalpopularvote.com:

The fact that serious candidates solicit every voter that matters was also demonstrated in 2008 by Nebraska’s 2nd congressional district (the Omaha area). Even though each congressional district in the country contains only 1/4% of the country’s population, the Obama campaign operated three separate campaign offices staffed by 16 people there. … Mitt Romney opened a campaign office in Omaha in July 2012 in order to compete in Nebraska’s 2nd district and … the Obama campaign was also active in the Omaha area.

…

In many cases, small states offer presidential candidates the attraction of considerably lower per-impression media costs …

Kamarck Explains

A bunch of points from Elaine Kamarck’s “Primary Politics”:

1. Turnout in Iowa has increased almost every year in which there’s a competitive contest. In 2008 227,000 Democrats participated in the caucus, as compared to 124,000 in 2004. Page 17. When candidates show up, participation goes up.

2. In the 1970s the caucus and convention system, “long a private or at most semi-public process, became, by law in both parties, a fully public system.” Pp 20-21. States can change the system.

3. “As the process became public it attracted the kind of attention and voter interest that was unheard of in prior days.” Page 21. If states allocated some or all of their electors to the national winner, then the nominees’ search for voters everywhere would attract huge attention and voter interest everywhere.

4. The primary system had led to consolidation of voting around certain days. It could lead to a national primary, which is favored by “substantially more than 50% of the American public [that] favors the simplest and most direct form of democracy.” Page 26. Similarly, well more than 50% favor simple, direct democracy as the way to choose the president in the general election. The cure for non-participation in politics is to let the people participate directly in a single national vote for president.

The State of the Union Shows how the Electoral College Distorts Our Policies

In the State of the Union, President Trump called out a few specific states that, according to him, were particularly harmed by U.S. trade deals:

“Another historic trade blunder was the catastrophe known as NAFTA. I have met the men and women of Michigan, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Indiana, New Hampshire, and many other states whose dreams were shattered by the signing of NAFTA.”

It is no coincidence that Trump’s list of states includes some of the most important battleground states that will decide the 2020 election. Under our current system, the president is free to ignore the needs of most Americans, focusing only on a few closely contested states. Our policies should be evaluated based on their overall impact on the nation, not just their impact on swing states.

Presidential Selection System Skews Policies Badly

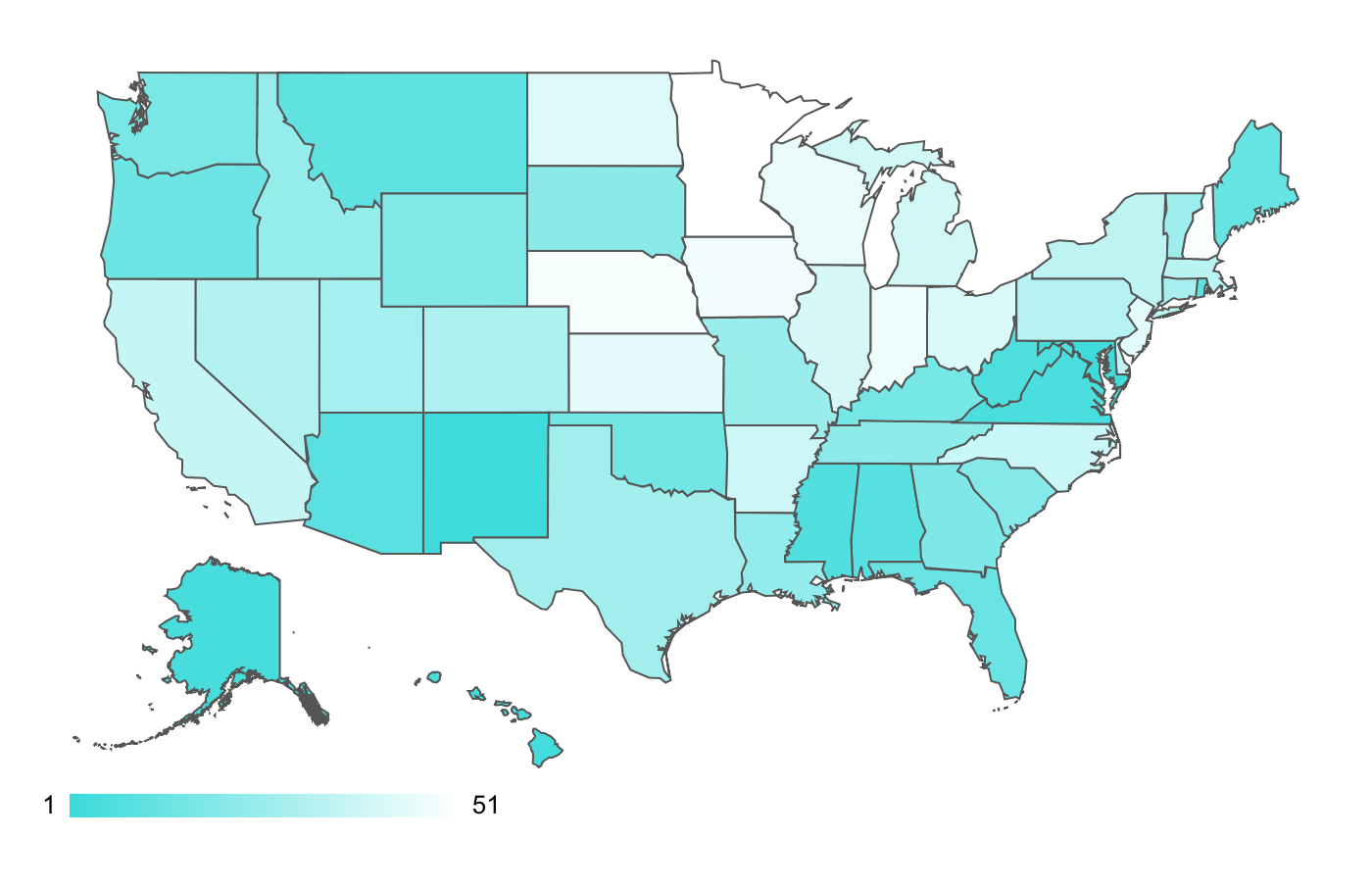

If you overlay against the map below the Electoral College, you’ll see that the Midwestern states critical to getting 270 electoral votes are more vulnerable to automation’s effects than the country as a whole:

It’s in the interest of all Americans to have forward-looking governmental policies for job creation. But the Electoral College system invites presidential candidates to promise reactionary, hostile, and ultimately useless responses to technological change.

It’s in the interest of businesses in the Midwest, as well as political leaders, to support the national popular vote as the means to choose the president. That’s the best way to get national job creation policies that are good for everyone.

Who gets hurt worst by the Electoral College? It's not Democrats — it's democracy

Here is Part II of the series on how the Electoral College hurts Americans from MEVC co-founder and CEO Reed Hundt at Salon.com:

“[T]here are about 50,000 lumberjacks in the United States. Their median income is less than $40,000 a year, and their work is extremely dangerous. Almost all of them live in states taken for granted by the presidential candidates. Certainly candidates for statewide office in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho must pay attention to this sector, but presidential candidates devote exponentially more attention to coal miners, who are almost exactly as poorly paid, work in as dangerous an occupation, and are as numerous as lumberjacks. Why? Because they matter to the voting outcome in Pennsylvania.

If every vote counted equally, coal miners would not matter to candidates any more than lumberjacks, or more than any other category of workers concentrated outside swing states.

…

Ideally, every state legislature would pledge some or all of its electors to support the winner of the national popular vote. But if a few states took this action, either by law or through a ballot measure, then the odds of any presidential candidate winning the Electoral College without winning the national vote would drop dramatically. Faced with likely defeat by pursuing an exclusive swing-state strategy, both campaigns would seek both to win the pluralities in as many states as possible and also to win the national popular vote.”

Turning Out Every Vote Counts a Lot

As the chart below shows, voter turnout can increase drastically if a race is closely contested and people know their vote is likely to matter. A close Senate race in Texas and a close gubernatorial race in Georgia drove turnout up 14 and 21 points, respectively, above the average:

So if the presidential candidates competed to win the national popular vote, then every voter in every state would know their vote mattered. Turnout on average would go up in the 40 states currently ignored by the two parties’ candidates. An increase of 14 to 21 points would translate to at least 20 million more votes.

The two parties would have to reshape their policies, reconsider their coalitions, and perhaps change their nominating rules in order to capture a winning share of the huge influx of participation.

The Midwest May Not Love the Wall

This chart from Gallup shows that twice as many Republicans as independents think immigration is the country’s top problem:

Because there is no way the incumbent president can be elected without a big share of independent votes, the natural question is why he has elevated the wall to such political attention.

But the chart shows national averages. The results in the states that determined the 2016 election – Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin – are now shaping President Trump’s policies.

At least in Michigan, whose electoral votes are critical to both parties’ nominees, independents do not agree with Trump’s insistence on a wall.

These independent Michiganders should support the move to have the national popular vote pick the president. They share the views of other independents in other states, and in numbers there is strength.

America's presidential elections are broken: Here's how to fix them

Read the latest from MEVC co-founder and CEO Reed Hundt at Salon.com:

“[I]f between 10 and 20 electors from likely Republican states or swing states were bound to the national winner, instead of the state plurality winner, the Republican nominee should decide to compete for a national victory. Correspondingly, if 10 to 20 electors from Democratic-leaning or swing states were bound to the national winner, then the Democratic nominee would compete for a national victory. It should be easy to put the question—do you want your state’s electors to be from the national winner’s slate?—on the ballot in enough states to make the candidates try to win the national election, for the first time in American history

…

The goal is to have candidates compete for every vote of every American, persuading everyone to participate and ensuring that the winner in the whole country becomes the president of the whole country. It can be achieved by the people themselves, acting through or in spite of their legislatures.”

The National Popular Vote is Good for the Country and Good for Connecticut

The editorial board of Connecticut newspaper The Day has published an editorial arguing that Connecticut should withdraw from the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (“NPVIC”). The editorial gives several arguments in support of its position, but none are persuasive.

The editorial board notes that in 2004, Democrat John Kerry won in Connecticut by 10.4 points, but that if the NPVIC had been in effect, “Connecticut would have assigned its seven electoral votes to Bush because he won the national vote by 2.4 points.” They argue that this would not have served Connecticut voters.

But the current system didn’t serve Connecticut voters either. All 693,826 Connecticut votes for Bush were thrown away. In addition, all the votes for Kerry over the 693,827 needed for plurality—163,662 votes—did not count either, because Kerry would have gotten Connecticut’s votes whether he won by one vote or by hundreds of thousands of votes. The fact that the election was “a landslide” in Connecticut was meaningless, and in fact rendered many votes in Connecticut pointless.

Under a national popular vote system, all the votes in Connecticut would have been counted, including the votes for Bush and the excess votes for Kerry. More importantly, the campaign itself would have been different, with both candidates reaching out to all voters instead of concentrating only on bringing out their bases in swing states.

The editorial argues that the “right way” to assure the candidates with the most votes wins would be to amend the Constitution.

But the Constitution does not mandate our current, winner-take-all system. In fact, Article II, Section 1 of the Constitution specifically leaves it to the states to decide how to allocate their electoral votes. There are multiple ways a state may allocate its votes, including splitting electoral college votes as Nebraska and Maine have done. It’s up to the states to decide what is the “right way” to allocate their votes.

Nor is it persuasive to argue that the Electoral College is supposed to protect small states like Connecticut.

That was certainly part of the intention—along with preserving the institution of slavery—but in reality, small states are ignored entirely under our current system unless they happen to be swing states. In fact, Connecticut is completely ignored under the current system. Presidential candidates never visit, nor do they pay attention to Connecticut’s particular concerns. The Electoral College is not making good on its promise to give a voice to small states.

Next, the editorial board writes; “Imagine the controversy if this plan was in place and the national vote was too close to call. The nation would face recounts in 50 states.”

The current system does not prevent chaos, as anyone who remembers the 2000 election will testify. Because it involves so many more voters, the national popular vote is much less likely to be too close to call than any given state’s vote. Moreover, all of the votes will be counted (and yes, possibly recounted) equally, instead of the entire country’s election turning on only a few votes in one state, as happened in 2000.

Next, they argue that the NPVIC would “encourage multi-candidate races” and raise the possibility of “a president being handed an electoral majority after getting, say, 35 percent of the vote, potentially without even winning a state.”

To the first point, many Americans would welcome a viable third party candidate. According to one poll, 68% of Americans say that two parties do not do an adequate job of representing the American people and that a third party is needed. As for the possibility of a winning candidate only getting 35% of the vote, that is already possible under the Electoral College. What’s worse, under our current system, one candidate could get 35% and still lose the election to a candidate with an even lower share of the votes!

Finally, they argue that Article I, Section 10 of the U.S. Constitution conflicts with the NPVIC: “No State shall, without the Consent of Congress … enter into any Agreement or Compact with another State.” However, this is not the type of compact that the Supreme Court has found requires congressional approval.

The NPVIC is good for Connecticut and good for the country. Under a national popular vote system, all votes will count equally and politicians will have to listen to all Americans, not just the select few in swing states.

Women and the Electoral College

In 2016 more women voted for the president then did men. And women preferred Clinton by a bigger margin than men preferred Trump. Obviously, if the United States had a democratic system the preference of women would have become president.

The chart below, showing what would happen if only women voted in the 2018 midterms, shows how the preference of women for the Democrats led to that party’s victory in the House of Representatives in 2018.

The chart also explains how the preferred choice of women in 2016 did not become the president. It may very well explain how the democratic nominee may not become president in 2020 unless some states allocate electors to the national popular vote winner.

The problem is the bizarre electoral college system in which the people in a few arbitrarily chosen states effectively pick the president.

Despite the huge Democratic preference among women nationally, in 2018, women in Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin were less supportive of that party. In many districts in these states women were still in the Democratic camp but statewide the female preference for Democrats was more muted than in the country as a whole.

These happen to be the swing states where the results of the 2020 election will be determined. Unless the system is changed.

Independent Schultz Needs to Fund Ballot Initiatives

Howard Schultz, lifelong Democrat and, at least for several decades, a billionaire, is thinking of running for president as an independent.

According to Axios, a Schultz adviser stated that:

“In the latest Gallup data, 39% of people see themselves as independents, 34% as Ds and 25% as Rs.

The adviser said research by the Schultz team shows a centrist independent would draw evenly from the Republican and Democratic nominees, and bring Trump down to a ‘statistical floor of 26-27-28 percent.’”

But hello, Schultz Adviser: the problem with your guy’s would-be candidacy is the Electoral College system. On a national level an independent, especially one willing to spend hundreds of millions of dollars out of a personal fortune ten times that amount, might harbor some hope of finishing first in a national three-person race, assuming that the Democratic and Republican nominees offered little appeal to the huge middle of the electorate.

But it is very unlikely that an independent would do well in the Electoral College. Most probable is that the independent who is a former Democrat, like Schultz, would guarantee the electoral victory to the incumbent.

The reason is that no independent can finish first in the solidly red states that comprise about 230 electoral votes for the Republican. The margins for the Republican nominee, whoever that is, are simply too big to be threatened by an independent, especially one who used to be a Democrat.

The Republican path to victory then runs through Florida, with 29 electors, leaving only 11 to be gained from multiple means – just Pennsylvania, just Michigan, or Wisconsin plus one of the three ways to get a single elector in Maine. If the independent ran strongly in these states, then perhaps the Republican nominee would not prevail in Pennsylvania or Michigan. But the Republican needs just the 11 more if Florida is the red bag of states.

Meanwhile the independent’s candidacy makes it nearly impossible for the Democratic nominee to get to 270. The Democratic base of electors is only about 211 electors, drawn mostly from solidly blue states like California, New York, and the combination of states in New England. An independent probably will gain the most votes from these states—and will need to do so to be competitive in the irrelevant national tally.

If the independent finishes first in any of the typically blue states, there aren’t enough electors in the swing states to give the Democrat, with a diminished base, a way to get to 270 electors.

If the independent somehow manages to stop the Republican from winning a plurality in Florida, then possibly the Republican also cannot get to 270 electors.

But here’s the kicker. If the Republican and Democratic nominee each fail to get to 270 electors, even if Schultz amazes everyone by winning the meaningless national tally, the House of Representatives then chooses the president.

Every state delegation has one vote. An untested constitutional issue is whether the votes would be cast by the existing House or the newly elected House. Currently, Republicans control a majority of state delegations, and they might well retain that position after 2020. For that reason, resort to the House would probably favor the Republican nominee.

Therefore, the Republican nominee will probably win the presidency.

Someone might want to encourage Howard Schultz to bankroll the ballot initiatives that in many states can let the people decide whether they want the popular vote winner always to be president. Then his candidacy could possible lead to his victory in 2020. Otherwise, with the current, crazy, antedated, anti-democratic system, he can do no more than guarantee victory for the Republican nominee.

Blame the System

As the Gallup chart below shows, Americans as described by their political views are fairly evenly balanced. Most are moderate to center right. Compromise is obviously the way to get things done.

But the presidential selection system motivates both parties to push turnout of a few voters in a few states in order to win all the electors in those swing states. Noisy divisiveness is the tactic that the swing state system calls for.

(The people in the swing states especially don’t like this.)

If a few disparate states awarded their electors to the winner of the national popular vote, like Ohio, the Dakotas, and Oregon, then by 2020 both parties would have to win nationally. To do so, they would have to reflect the views of the majority of voters everywhere. The result would be more pragmatic, effective candidates, and a welcome harmony between the wishes of the majority of the people and the behavior of the winner as president.

Not Quite

“[T]he minority share of the electorate is growing,” and this favors the Democrats, assert Levitsky & Ziblatt. They then explain that the Republican response has been to limit participation by, inter alia, pushing for voter ID laws. These have “only a modest effect on turnout. But a modest effect can be decisive in close elections…” Pages 183-85.

Two comments.

First, increase in minority participation may be important to the national popular vote, but of course that is irrelevant to the question of who wins the presidency. The increase in minorities in the overall population arguably has motivated Republicans to vote for their nominee in swing states more than it has favored Democrats in swing states.

Second, the “modest effect” is especially critical in swing states. In a national popular vote system, voter ID laws would not matter much because their “modest effect” would be unlikely to alter the outcome.

The Shutdown Hurt Swing States Less—And it’s not a Coincidence

Take a look at this map of states most and least affected by the government shutdown:

Now take a look at the list of the closest states in the 2016 election. A cursory glance shows a remarkable amount of overlap between critical, close states and states minimally affected by the government shutdown. The decisive states of Minnesota, Wisconsin, Michigan, and New Hampshire are among the states impacted the least.

The shutdown hurt all of America, but it did not hurt all Americans equally. The shutdown was most harmful to the states both parties can afford to ignore—D.C. and Maryland on the left; Alaska and Mississippi on the right—but largely spared the few voters that matter.

Though many have referred to Trump’s decision to shut down the government as a “gamble,” it was a gamble for which Trump understood the odds. He knew who would feel the pain and who would not. An increasingly large majority of Americans disapprove of the shutdown and held Trump responsible. But as any president or candidate knows, it is the opinion of voters in swing states that counts. The opinion of the country overall simply does not matter.

At least not yet.